Le parole di Shakespeare

Le parole, i testi e le idee di John Florio utilizzate nelle opere di Shakespeare

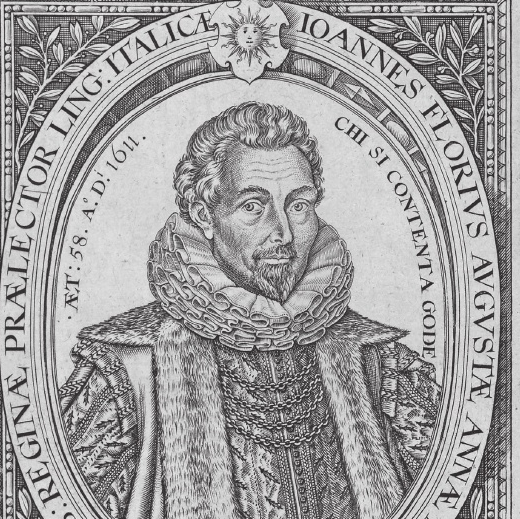

John Florio & Leicester's Men: i suoi contatti con il teatro.

Nel 1578 John Florio pubblicò la sua prima opera, First Fruits, che contiene quattro poemi dedicatori

scritti dall'intera compagnia dei Leicester's Men. Sono Richard Tarlton, Robert Wilson, Thomas Clarke

e John Bentley. Ringraziano John Florio per aver contribuito a portare i romanzieri italiani nel teatro inglese.

Le dediche dimostrano che Florio era in contatto con la compagnia teatrale molto prima dell'arrivo in città di

William Shakespeare; le poesie indicano che Florio era il tutore e maestro della compagnia teatrale e aveva

una collaborazione con loro per le commedie. Giulia Harding e Chris Stamatakis1hanno sostenuto che John Florio

faceva parte di una "rete teatrale" con la compagnia dei Leicester's Men. Stephen Greenblatt 2afferma anche

che ci sono prove che "già nei primi anni del 1590 era un uomo molto familiare con il teatro".

3

3

Richard Tartlon per Florio

"If we at home, by Florios paynes may win,

to know the things that travailes great would aske:

By openyng that, which heretofore hath bin a daungerous journey,

and a feareful taske.

Why then ech Reader that his Booke doe see,

Give Florio thankes, that tooke such paines for thee."

Robert Wilson per Florio

"The pleasant fruites that FLORIO frankly yeeldes, unseene tyl now, saue in Italian soyle:

May quickly florish in our English fieldes,

if in this woorke we take but easie toyle.

He sets, he sowes, he plants, he proynes with paine,

the seedes, and Cienes farre fet from forraine landes:

And geues vs (idle) both the stocke and graine,

even his firste fruites the ioy of labouring handes.

We geue hym nought, if we can not deuise

to giue him thankes, that may hym wel suffice."

Shakespeare’s proverbs and John Florio’s proverbs

Florio's First Fruits (1578), Second Fruits (1591) and Giardino di Ricreatione (1591)

contengono proverbi che oggi sono erroneamente attribuiti a Shakespeare ma originariamente

furono scritti da John Florio.

Clara Longworth de Chambrun, studiosa di Shakespeare, nel suo libro "Shakespeare, Actor-Poet"4 ha riportato le

somiglianze tra i due scrittori riguardo ai proverbi:

- Florio: Fast bind fast find (Second Fruits, Folio 31).

- Shakespeare: Fast bind fast find, a proverb never stale in thrifty mind (Merchant of Venice, Act II, sc. 5).

- Florio: All that glistreth is not gold (SF, Folio 32).

- Shakespeare: All that glitters is not gold, golden tombs do dust enfold (Merchant of Venice, Act II, sc. 5).

- Florio: More water flows by the mill than the miller knows (SF, Folio 34).

- Shakespeare: More water glideth by the mill than wots the miller of (Titus Andronicus, Act II, sc. i).

- Florio: When the cat is abroade the mise play (SF, Folio 33).

- Shakespeare: Playing the mouse in absence of the cat (Henry IV, Act I, sc. 2).

- Florio: He that maketh not marreth not (SF, Folio 27)

- Shakespeare: What make you nothing? what mar you then? (As You Like It, Act I, sc. i).

- Florio: An ill weed groweth apace (SF, Folio 31).

- Shakespeare: Small herbs have grace, great weeds do grow apace (Richard III, Act II, sc. 4).

- Florio: Make of necessity virtue (SF, Folio 13).

- Shakespeare: Make a virtue of necessity (Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act IV, sc. 2).

- Florio: Give losers leave to speak (SF, Folio 33).

- Shakespeare: But I can give the loser leave to chide, and well such losers may have leave to speak (Henry VI, Part II, Act III, sc. i).

- Florio: It is Labour lost to speak of love (SF, Folio 71),

- Shakespeare takes as a title: ‘‘Love’s Labour’s Lost.”

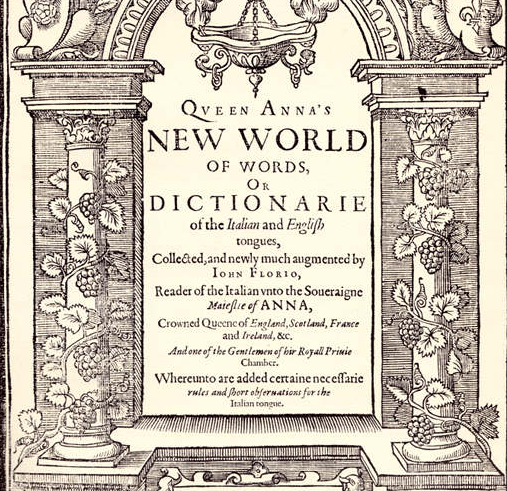

- Florio: much a doe about nothing (Queen Anna's New World of words, 1611)

- Shakespeare takes as a title: Much Ado About Nothing

- Florio: Tutto è bene, che riesce bene (Giardino di Ricreazione, 1591)

- Shakespeare takes as a title All's Well That Ends Well

- Florio: Necessity hath no law (SF, Folio 31).

- Shakespeare: Nature must obey necessity (Julius Cesar, Act III, sc. 3).

- Florio: Lombardy is the garden of the world (Second Fruits)

- Shakespeare: I am arrived for fruitful Lombardy, The pleasant garden of great Italy. (The Taming of the Shrew, 1.1.3–4)

- Florio: A gallant death doth honour a whole life (SF, Folio 34).

- Shakespeare: Nothing in life became him like the leaving of it (Macbeth, Act I, sc, i).

- Florio: The end maketh all men equal (SF, Folios 33).

- Shakespeare: One touch of nature makes the whole world kin. (Troilus and Cressida, Act III, sc. 3).

- Florio: That is quickly done that is done well.

- Shakespeare: If ‘twere done when ‘tis done ‘twere well kwere done quickly (Macbeth, Act I, sc 7).

- Florio: Venitia, chi non ti vede non ti pretia ma chi ti vede bene gli costa. (Second Frutes) (Venice, he who seeth thee not praiseth thee not, but he who seeth thee it costs him dear - First Fruits, Folio 34).

- Shakespeare: I may say of thee as the traveller doth of Venice: Venetia Venetia, chi non ti vede non ti pretia. Old Mantuan, who understandeth thee not, loves thee not. (Love's Labour's Lost, Act IV, sc 2).

- Besides these examples, Shakespeare refers some thirty times to proverbs in such phrases as these:

- Thereof comes the proverb: Blessings on your heart, you brew good ale (Two Gentlemen of Verona).

- While the Grass grows —The proverb is somewhat musty (Hamlet).

- Like the poor cat in the adage {Macbeth) .

- I am proverb’d with a grandsire phrase {Romeo and Juliet). C'è anche, in Enrico V, ciò che Shakespeare chiama "rapid venew of wit", che è difficile da capire senza la spiegazione di Florio che "Quattro è la compagnia del Diavolo" {Compagnia di quatro, compagnia del Diavolo) I disputanti in Shakespeare sono quattro: "ll will never did well," dice uno. "I’ll cap that proverb with 'there's flattery in friendship," replica il secondo. "And I will take up with: 'Give the Devil his due," ribatte il terzo "Well placed, there stands your friend for the devils," e il misterioso riferimento è spiegato. Da questi paralleli, è ovvio che sia Shakespeare che Florio usassero le stesse tecniche di conversazione, lo stesso metodo di proverbi nel discorso colloquiale, gli stessi detti spiritosi, sillogismi, ragionamenti filosofici, e avevano anche la stessa opinione su vari argomenti.5

Dialoghi di Shakespeare e John Florio, un confronto

I dialoghi che Florio scrisse in First Fruits(1578) e Second Fruits (1591), differivano dai suoi predecessori.

Florio, infatti, non scriveva manuali di lezioni di lingua per scolaresche o principianti della lingua.

Mirava piuttosto alla nobiltà, scrivendo dialoghi drammatici sull'amore, le donne, il teatro, la filosofia;

argomenti che non possono essere trovati nei manuali di lezione di un'altra lingua. Molti studiosi di Florio

hanno sottolineato che le opere di Florio contengono dialoghi drammatici che "devono qualcosa alla commedia

italiana del Cinquecento".6

Nella biografa di Shakespeare e Florio, Clara Longworth de Chambrun nel secondo capitolo del suo libro "Giovanni Florio,

un apôtre de la renaissance en Angleterre a l'époque de Shakespeare"7 ha fatto un'ampia analisi dei dialoghi drammatici

di Florio di First Fruits e Second Fruits facendo un confronto con i dialoghi di Shakespeare, e sottolineando le

somiglianze tra i due scrittori. La stessa analisi fu fatta anni dopo da Rinaldo Charles Simonini nel suo libro

"Italian Scholarship in Renaissance England".8 Alcuni passaggi possono essere letti di seguito.

Ne i Due gentiluomini di Verona, Valentine discute della sua dama con Speed. Tutta la scena, sottolinea Simonini9,

è molto simile al dialogo di Florio su “Amorous talke” nel capitolo 14 dei Firste Fruites.10

Il capitolo 17 di First Fruites, “To talke in the darke”11 richiama l'atmosfera della scena iniziale dell'Amleto di Shakespeare.

Altre somiglianze si possono trovare nei sillogismi e nei detti spiritosi che si trovano sia in Shakespeare

quanto nei manuali di Florio.12 Simonini sottolinea anche come Shakespeare inizi il suo dialogo sulle nazionalità

nel Mercante di Venezia nello stile consueto Florio:

- Shakespeare, Il mercante di Venezia: Por. I pray thee, over name them; and as thou namest them, I will describe them; and, according to my description, level at my affection.

- John Florio, First Fruites, pagina 70: Tel me of curtesie, if you know the customes of certaine nations, I know you know them.13

- In Second Frutes, la sapienza mondana data da Stefano a Pietro, il viaggiatore neofita, è molto simile al consiglio di Polonio a Laerte in Amleto14, "the high regard for scholars manifest in this same dialogue is of particular interest because both Florio and Shakespeare's Hamlet show the same respect for actors."15

- Inoltre, il lungo dialogo del capitolo 12 di Second Frutes è una sorta di compendio di argomenti sull'amore e le donne, sia a favore che contro. Sembrerebbe che Shakespeare faccia eco ai Second Frutes nei suoi argomenti a favore e contro l'amore e la scrittura di sonetti in Love Labour's Lost. Frances Amelia Yates, studiosa di Shakespeare e Florio, in "A Study of Love Labour's Lost"16, pagina 24, sottolineaa come Shakespeare non solo ha studiato attentamente questo dialogo, ma conosceva anche la storia che c'era dietro.

- Sia Florio che Shakespeare condividono anche lo stesso tema dell'ingiustizia sociale, ed entrambi scrivono letteratura antifemminista.

- Per esempio: Shakespeare, la battuta di Iago con Desdemona nell'Otello: Iago. Dai; siete immagini all'aperto, ragazze nei vostri salotti, gatti selvatici nelle vostre cucine, santi nelle vostre ferite, diavoli offesi, attori nella vostra casalinga e casalinghe nei vostri letti. (Otello, II. i. 110-113) Florio, Second Frutes: Le donne sono il purgatorio delle borse degli uomini; Il paradiso dei corpi degli uomini; l'inferno delle anime degli uomini. Le donne sono sante nelle chiese; angeli all'estero; a casa diavoli;Alle finestre sirene; alle porte pyes; e nei giardini capre.

- Al contrario, c'è una discussione sulla bellezza femminile in Second Frutes, in particolare sulle

"partes che una donna dovrebbe avere per essere considerata più bella".

Florio:

- In choyse of faire, are thirtie things required For which (they saie) faire Hellen was admired, Three white, three black, three red, three short, three tall, three thick, three thin, three streight, three wide, three small, white teeth, white hands, and neck as yvoire white, black eyes, black browes, black heares that hide delight; Redd lippes, red cheekes, and tops of nipples red, Long leggs, long fingers, long locks of hear head, Short feete, short eares, and teeth in measure short, Broad front, broade brest, broad hipps in seemely sort, Streight leegs, streight nose and streight her pleasure place, Full thighes, full buttocks, full her bellies space, Thin lipps, thin eylids, and beare thin and fine, Smale mouth, smale waste, small pupils of her eyne, Of these who wants, so much of fairest wants, And who hath all, her beautie perfect vauntes.

- Colpisce il parallelo nella struttura, nella fraseologia e nell'insolito metro spondaico

tra il poema di Florio e la descrizione di Shakespeare di un eccellente cavallo in Venere e Adone.17

Shakespeare:

Round-hoof'd, short-jointed, fetlocks shag and long, Broad breast, full eye, small head and nostril wide, High crest, short ears, straight legs and passing strong, Thin mane, thick tail, broad buttock, tender hide: Look, what a horse should have he did not lack, Save a proud rider on so proud a back. (lines 295-300) - Un'ulteriore illustrazione sarà sufficiente a sottolineare la varietà di notevoli parallelismi e somiglianze tra First e Second Fruits di Florio e le opere di Shakespeare. In First Fruites c'è un dialogo sulle virtù del vino.18 Il discorso di Falstaff sulle virtù del sacco si avvicina molto al dialogo di Florio. Simonini nota anche come "Shakespeare usa le stesse parole o significati attorno ai quali costruisce la similitudine: vapori (umori), arguzia, sangue, cuore, cervello (spiriti) e apprendimento (memoria)".19

[1]url=http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781315618401, title=Shakespeare, Italy, and Transnational Exchange, date=2017-05-12,

publisher=Routledge, doi=10.4324/9781315618401, isbn=978-1-315-61840-1, De Francisci Enza, Stamatakis Chris

[2]Stephen Greenblatt, Will In The World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, Pimlico, 2005, p. 227.

[3]Florio John, url=https://www.google.it/books/edition/Florio_s_First_fruites/ChvPAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=first+fruites+john+florio&printsec=frontcover%7Ctitle=Florio's

First fruites: facsimile reproduction of the original edition, Re Arundell del, date=1936, publisher=Taihoku Imperial University, language=it

[4]Marshburn J. H.,Chambrun Clara Longworth de, date=1960, title=Shakespeare: A Portrait Restored, url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/40114402,

journal=Books Abroad, volume=34, issue=1, pages=74, doi=10.2307/40114402, jstor=40114402, issn=0006-7431

[5]Bradbrook M. C., Simonini R. C., date=January 1953, title=Italian Scholarship in Renaissance England, url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2866566,

journal=Shakespeare Quarterly, volume=4 issue=1, pages=93, doi=10.2307/2866566, jstor=2866566, issn=0037-3222

[6]Boutcher Warren, date=1997-01-XX, title='A French Dexterity, & an Italian Confidence', url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/ref_1997_2_1_004, journal=Reformation, volume=2,

issue=1, pages=39–109, doi=10.1179/ref_1997_2_1_004, issn=1357-4175

[7]DE. CHAMBRUN, CLARA LONGWORTH, url=https://www.worldcat.org/title/giovanni-florio-un-apotre-de-la-renaissance-en-angleterre-a-lepoque-de-shakespeare/oclc/1284622424&referer=brief_results,

title=Giovanni florio, un apotre de la renaissance en angleterre a l'epoque de shakespeare (classic ... reprint)., date=2016, publisher=FORGOTTEN Books,

isbn=978-1-334-05264-4, oclc=982936533

[8]Charles Simonini, R.C. Rinaldo, url=https://www.worldcat.org/title/italian-scholarship-in-renaissance-england/oclc/906121956, title=Italian scholarship in Renaissance England,

date=1952, publisher=University of North Carolina, oclc=906121956

[9]Bradbrook M. C., Simonini R. C., date=January 1953, title=Italian Scholarship in Renaissance England, url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2866566, journal=Shakespeare Quarterly, volume=4,

issue=1, pages=93, doi=10.2307/2866566, jstor=2866566, issn=0037-3222

[10]Shakespeare: "Val. I have loved her since I saw her; and I still see her beautiful Speed. If you love her, you cannot see her.

Val. Why? Speed. Because Love is blind. O, that you had mine eyes: or your eyes had the lights they were wont to have when you chid at

Sir Protens for going ungartered! (II. i. 73-79)" John Florio: "Oh deare brother, I am in love With a woman, the which is So cruel,

that she wyl neither see me, neither heare me, the which thing maketh me almost die. Alas brother, will you let love Vanquish you,

the which is but A boy, blind & seeth not? Alas, for al that he is but a boy, he hath great strenght, for al that he is blynd,

he seeth. But how can this thing be? Aske of them that have made proofe of it.

[11]John Florio, First Fruites: "Ho, ho, who goeth there? I am your friend. What is your name: I am called A. You are well met. And so be you also. Pardon me, for I know you not.

I beleve you certis. Where have you been so late? I have ben forth at supper with A friend of myne."

[12]John Florio, First Fruites, page 37: Wel, tel me which is the oldest thing that is. Truely, I know not. I pray you tel me. God is the

oldest thing. Because he hath alwayes ben, & never had beginning… You have not erred: but tel me, what is the swiftest thing that is?

The swiftest thing that is, I beleeve it be the mynd of man, for in a moment he is here, and now he is there, now in one place, now in another.

" The gravediggers in Hamlet use the same device to amuse themselves while they work: "Frist Clown. I’ll put another question to thee: if thon

answerest me not to the purpose, confess thyself-- Second Clown. Go to. First Clo. What is he that builds stronger then either the mason, the

shipwright, or the carpenter? Sec. Clo. The gallow-maker; for that frame outlives a thousand tenants. (V. i. 42-50; see also V- i. 51-68).

" Italian Scholarship in Renaissance England, Rinaldo C. Simonini · 1952, University of North Carolina, p. 92.

[13]Bradbrook M. C., Simonini R. C., date=January 1953, title=Italian Scholarship in Renaissance England., url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2866566,

journal=Shakespeare Quarterly, volume=4, issue=1, pages=93, doi=10.2307/2866566, jstor=2866566, issn=0037-3222

[14]Florio, Second Frutes, pp. 93-111, Hamlet, Iiii – Simonini pg. 95

[15]Rinaldo, Charles, Simonini, Italian Scholarship in Renaissance England, Rinaldo C. Simonini · 1952, University of North Carolina, p. 95

[16]Verfasser Yates, Frances A. 1899-1981, url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/1106768408, title=A study of Love's labour's lost, date=2013,

publisher=Cambridge Univ. Press,isbn=978-1-107-69598-6, oclc=1106768408

[17]Venus and Adonis (Titian), date=2020-12-23, url=https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Venus_and_Adonis_(Titian)&oldid=995903735, work=Wikipedia,

language=en, access-date=2021-04-16

[18]John Florio, First Fruites, p. 28

[19]Rinaldo Charles Simonini, Italian Scholarship in Renaissance England, Rinaldo C. Simonini · 1952, University of North Carolina, page 99

Torna in testa